One of the reasons St Patrick is Ireland’s national saint is because we have his own, fifth-century accounts of his mission to Ireland written as a Roman citizen and an ex-slave who was captured as a teenager by Irish pirates.

We also have seventh-century and later lives of the saint which talk of his travels throughout the island and his conversion of kings and peoples along the way. One of the longest and most evocative of these lives is written in Irish and is known as the Bethu Phátraic or the Tripartite Life of Patrick. It is a multi-period text with some elements dating to the period of the early foundation of Limerick city by Vikings and the career of Brian Boru’s father, Cennétig mac Lorcáin, in the first half of the tenth century. In the eleventh century, three sermons were added to break the text up into three sections – one for each of the three days of the celebration of the saint’s life and this is why it became known in English as the Tripartite Life. It is this life which provides our first detailed medieval account of Patrick’s travels in Munster, an account which belongs to the third day of the medieval festivities. This third section was devoted to the miracles of St Patrick and was introduced by Psalm 67:36 - God is wonderful in his saints : the God of Israel is he who will give power and strength to his people.

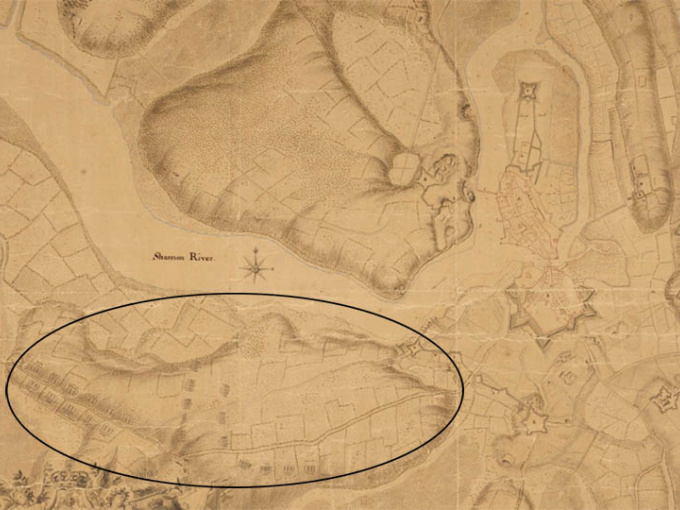

Patrick’s travels through Limerick according to Bethu Phátraic.

Patrick’s travels through Limerick according to Bethu Phátraic.

Patrick’s travels in Munster begin at Cashel where he converts King Oengus mac Nad-fróich, ancestor of the Eoganacht kings of the province. Famously, Patrick is distracted during the baptism and inserts the spike of his crozier into the king’s foot. When he realises this, and to make up for the damage, he blesses the king’s descendants, saying no king of Cashel will die of wounds until the time of Cenn Gécan (who died in 901).

Patrick then travels to Kilfeakle where he loses a tooth which subsequently becomes a famous relic: Cell Fiachla or the Church of the Tooth. He subsequently arrives in the kingdom of the Uí Cuanaigh (modern day Coonagh) stretching in this era from Pallasgreen up to the north of Doon. While there he blesses the women of Pallas, turning rushes into chives so as to provide a pregnant woman with nutritious food. Even more interestingly, he instructs two local saints to raise the local king’s son from the dead “and there were stones erected in their memory at that place: Patrick and Ailbe (of Emly) and Bishop Ibair and the little boy. This seems to be a clear reference to the prehistoric stone row on the hill of Lackanagoneeny as can be seen on the Megalithic Monuments of Ireland website.

Lackanagoneeny Stone Row

Lackanagoneeny Stone Row(Thanks to the O'Doherty family for access to the monument)

Patrick then travels to the area between Ballyneety and Limerick City where at Knockea he meets the young Nessan whom he ordains as deacon and who subsequently goes on to found the important monastery of Mungret. He blesses the people of east Clare who travel down the Shannon to meet him at Donaghmore and then he goes to the site of Fininne, from where he blessed the people of Thomond more generally. This placename is now unknown but Father Edmund Hogan, in 1910, suggested in his Onomasticon Goedelicum that it was the site of the hill on which Mary Immaculate College and the old convent of Mount St Vincent now stands. Certainly as one looks down the slope of South Circular Road one can see the hills of Clare in the background. An early map of the 1691 siege of Limerick by the Fleming Jan de Bodt shows the hill in all its glory before the modern buildings were erected.

Patrick leaves Fininne and goes to Singland where he baptises an early ancestor of King Brian Boru before heading off for Knockpatrick and Ardpatrick. He then visits the area around Lorrha before leaving the people of Munster with his blessing. His visit to the hill on which Mary Immaculate now stands is thus part of an itinerary concentrating particularly on east Limerick. It is a vivid reminder of the importance of Mungret and its surrounding district in the very early records of the churches and saints affiliated with Patrick and Armagh. Given the college’s role promoting excellence in teaching and learning, it is only fitting that our national saint, whose own writings lay such stress on the art of reading, should be remembered as having walked the very hill on which our college buildings still stand.

Translation of Patrick’s blessing with a photograph of the Harry Clarke depiction of St Patrick from the church of Cloughjordan.

Translation of Patrick’s blessing with a photograph of the Harry Clarke depiction of St Patrick from the church of Cloughjordan.

Patrick’s blessing on the people of Munster in Bethu Phátraic

Bendacht Dé for Mumain - feraib, maccaib, mnaїb,

Bendacht forsin talmain do-beir torud dáїb.

Bendacht for cech n-indmas gignes fora mrugaib

Cen nech for-ré cobair, bendacht Dé for Mumain

Bendacht fora mbenna fora lecca lomna

Bendacht fora nglenna bendacht fora ndromma

Gainem lir fo longaib robat lir a tellaig

I fánaib, i réidib i sléibib, i mbennaib

By Dr Catherine Swift, Department of History

A video of the lecture on which this blog is based is to be made available on the IICS website.